- Home

- Stalag 13 Today

- Stalag 13 History

History of the Real Stalag 13

Stalag 13 didn't just exist in the celluloid world of Hogan's Heroes.

There really was a POW camp called Stalag 13 (or Stalag XIII C) on the outskirts of Hammelburg, about 50 miles (80 km) east of Frankfurt.

World War II History

For World War I camp history and photos, see WWI history below.

Beginnings of the Camp

Sign for German Army Camp

Sign for German Army CampIn 1893, the Kaiser created a training camp for German soldiers in a large forested area about 2.5 miles (4 km) south of Hammelburg.

This training area was called Lager Hammelburg (or Camp Hammelburg) and it still goes by that name.

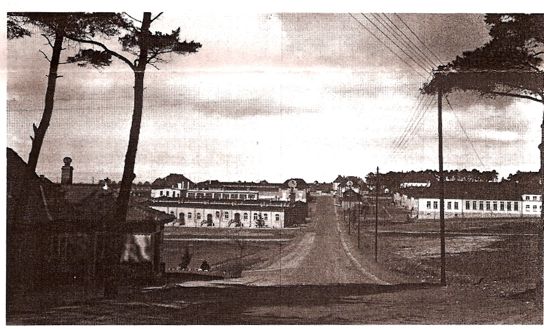

Lager Hammelburg and the town of Hammelburg, ca. 1917

Lager Hammelburg and the town of Hammelburg, ca. 1917(Truppen-Übungsplatz is the camp)

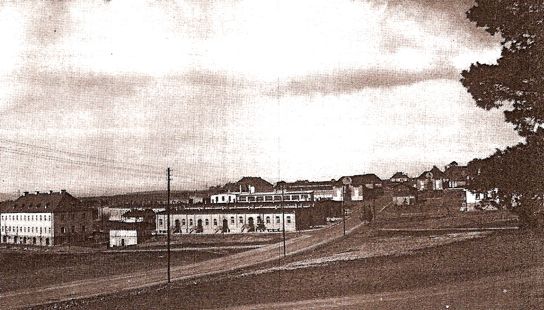

Camp and town of Hammelburg (reverse view of above)

Camp and town of Hammelburg (reverse view of above)During World War I, the camp was used to house Allied prisoners of war and in 1920, a Children's Home was established on the premises.

The Home for poor children was run by the Benedictine nuns and expanded over the years to take over many of the buildings. When it closed in 1930, over 60,000 children had been cared for there.

World War I POW Camp

Prisoners of many nationalities were held in Lager Hammelburg during World War I. Below are some postcards and photos of the camp from 1917-1919.

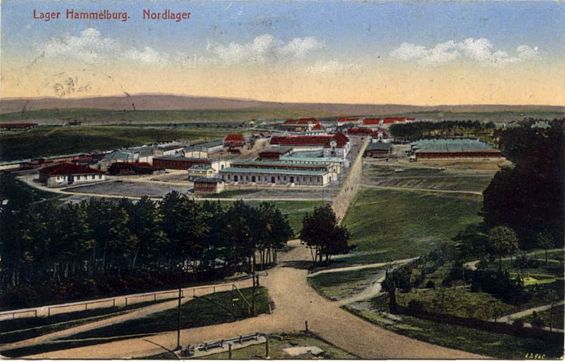

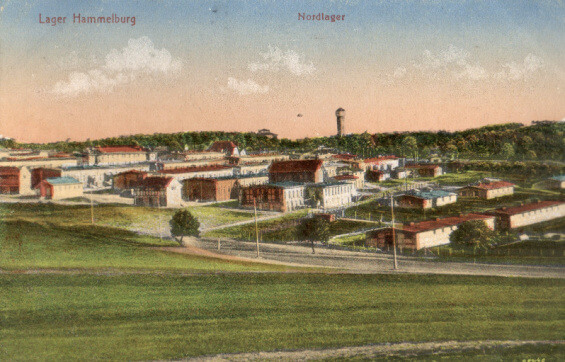

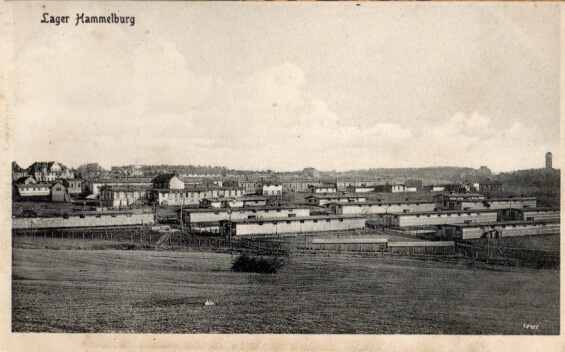

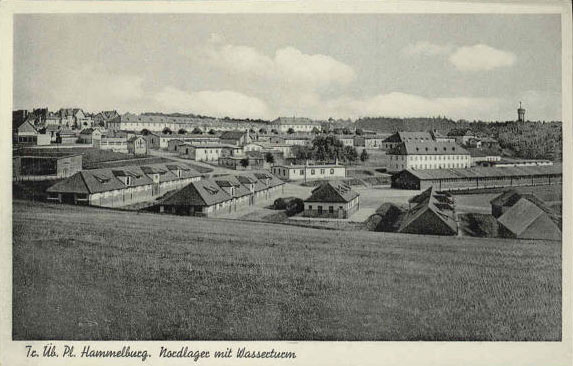

Two postcards and a photo of the Nordlager, or North Camp:

Lager Hammelburg in 1917: Nordlager

Lager Hammelburg in 1917: Nordlager Lager Hammelburg, Nordlager

Lager Hammelburg, Nordlager Lager Hammelburg, ca. 1917. Nordlager

Lager Hammelburg, ca. 1917. NordlagerDuring World War II, the Nordlager was used to house officer POW's and was called Oflag 13B.

The enlisted men were held in Stalag 13C, in the Südlager, or South Camp.

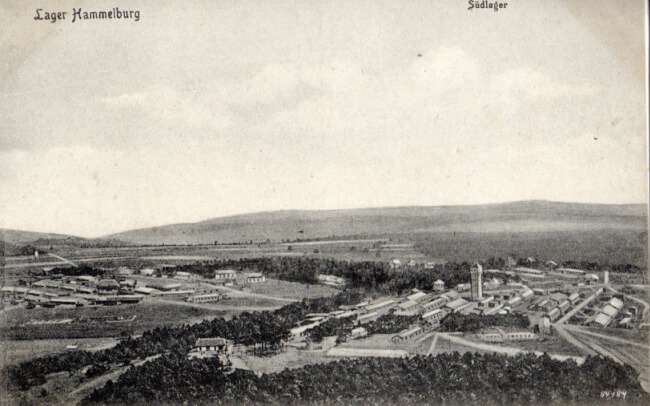

And a view of the Südlager, the future Stalag 13:

Lager Hammelburg, Südlager, ca. 1917

Lager Hammelburg, Südlager, ca. 1917The guard tower (below) appears at the rear of the Nordlager images and on the right in the Südlager image, above.

Guard Tower at Lager Hammelburg, ca. 1917

Guard Tower at Lager Hammelburg, ca. 1917Post card, closer view of the POW housing:

Lager Hammelburg POW barracks, ca. 1917

Lager Hammelburg POW barracks, ca. 1917Administration buildings at the camp:

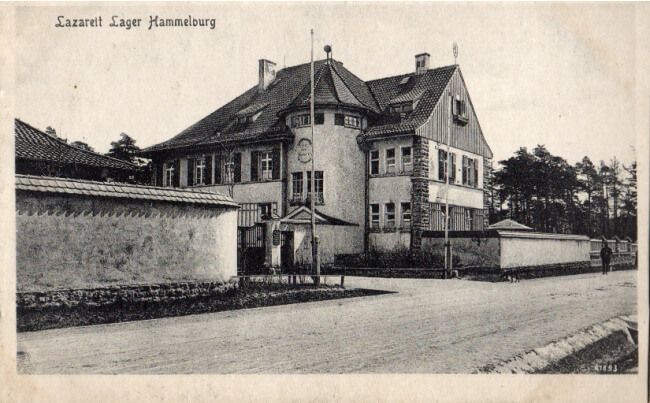

Lager Hammelburg Lazarett Building (hospital)

Lager Hammelburg Lazarett Building (hospital) POW Camp Offices

POW Camp OfficesThe three buildings above: the Provianamt (Provision Office), the Garnisonverwaltung (Garrison Office), and the Postamt (Post Office)

World War I POW's

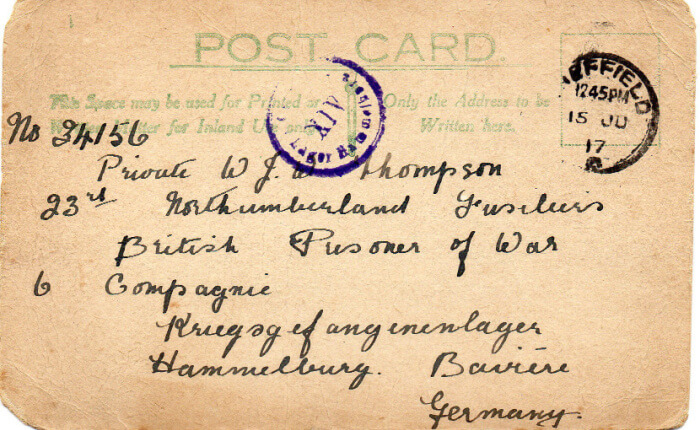

A great nephew of one of the English POW's in Lager Hammelburg during World War I has generously shared the photos and camp postcards received by his family during the war.

His great uncle, Walter Thompson, was a private in the Northumberland Fusiliers, and was captured on April 28, 1917. He was a prisoner in Lager Hammelburg, survived the war, and died in 1938.

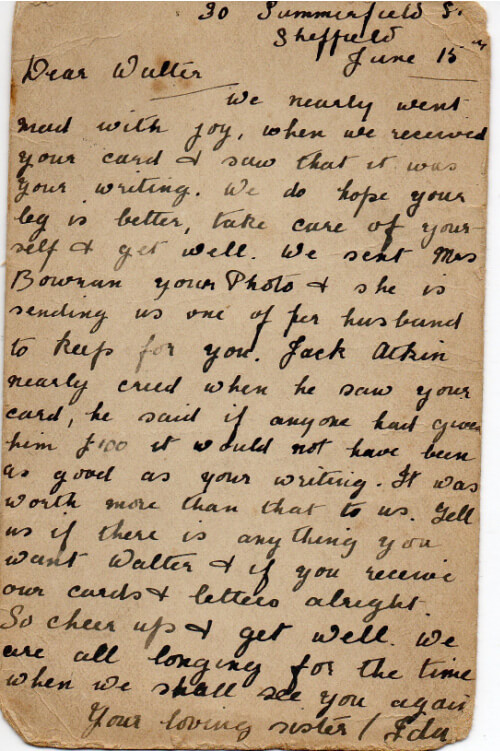

Walter's sister wrote to him in the camp after receiving news he was there:

June 15th 1917

Dear Walter,

We nearly went mad with joy, when we received your card & saw that it was your writing. We do hope that your leg is better, take care of yourself & get well. We sent Mrs Bowman your photo & she is sending us one of her husband to keep for you. Jack Atkin nearly cried when he saw your card, he said “if anyone had given him £100 it would not have been as good as your writing. It was worth more than more than that to us. Tell us if there is anything you want Walter & if you receive our cards & letters alright. So cheer up & get well. We are all longing for the time when we shall see you again.

Your loving sister

Ida.

The actual letter, on a post card

The actual letter, on a post cardThe reverse of the postcard-letter shows the Lager Hammelburg postal stamp:

Many (or all) of these photos were done by local photographers in Hammelburg and made into postcards for the prisoners to mail home.

Private Walter Thompson

Private Walter Thompson Back of Thompson's postcard photo

Back of Thompson's postcard photoSome of the photos were taken in August of 1918.

Walter Thompson is the first one in the front row.

Walter Thompson is the first one in the front row.Other POW's who have been identified are Alfred Roberts, middle of front row, and A. Stroud, second in back row (above).

Alfred Roberts

Alfred Roberts Rifleman A. Stroud

Rifleman A. Stroud Walter Thompson is the second one in the front row.

Walter Thompson is the second one in the front row.Alfred Roberts is in the back row, second from the end, and A. Stroud is the first one in the front row (above).

More group photos of WWI POW's in Hammelburg

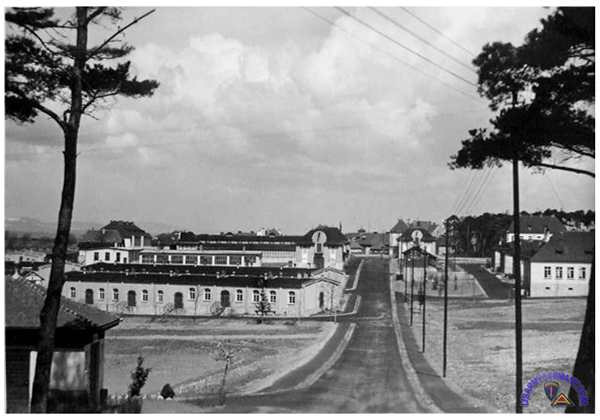

Just before WW2

Here is how the camp looked in 1938 when an artillery regiment was stationed there:

Future Stalag 13C (or rather Oflag 13B), 1938

Future Stalag 13C (or rather Oflag 13B), 1938 Lager Hammelburg, 1938

Lager Hammelburg, 1938Three more views of the camp were contributed by Dr. John Caruso.

Lager Hammelburg

Lager Hammelburg Nordlager Hammelburg

Nordlager Hammelburg Lager Hammelburg

Lager HammelburgAn expansion of the camp in 1938 swallowed two nearby villages. The ghost town of Bonnland is still there and is now used for urban warfare training. (See German Army video.)

World War 2 in Hammelburg

Stalag 13C is Born

Gates of Stalag 13, 1945

Gates of Stalag 13, 1945In the summer of 1940, the southern end of the camp was prepared for prisoners of war from the enlisted ranks.

The camp was called Stammlager XIII C, or Stalag XIII C for short, and wooden barracks were built to house POWs of a variety of nationalities.

The prisoners arrive...

After the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, several hundred captured American officers were sent to Oflag 13B. More Americans started arriving from camps in the east as the Russian army advanced.

The Lager held over 30,000 POW's, with the Russians as the largest group, and thousands of Serbian soldiers as well. As required by the Geneva Convention, different nationalities were housed separately.

Junior enlisted prisoners, corporal and below, were required to work. These POW's were assigned to work units in neighboring factories, farms and forests. They lived outside the camp and were guarded by a battalion of Home Guards (Landschützen).

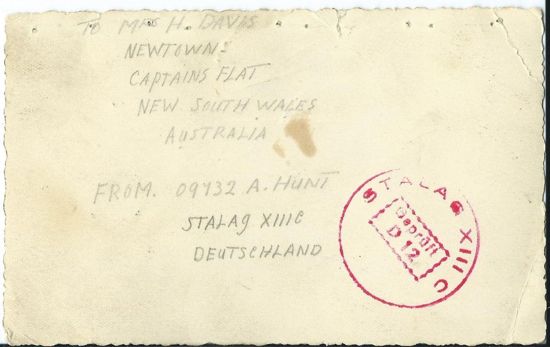

Australian & New zealand POWs in Stalag XIIIC

Australian POWs at Stalag 13C

Australian POWs at Stalag 13CThe third man from the right, bottom row, is Arthur Hunt, father-in-law of the contributor of the photo. Below is the reverse side of the photo, with the official Stalag XIII C stamp.

Other side of the above photo

Other side of the above photoThe man in the bottom row, far left, in the above photo is Jack S. Dell, from New Zealand (identified by his daughter). He joined an Australian unit before going overseas. He spent most of the war at Stalag XIII C and told his daughter lots of stories about his life in the camp.

One of the stories was that he volunteered to be a baker at the camp (with no experience), not because he was a baker, but because the man standing next to him was a baker who was too scared to step forward and say so! He then quickly volunteered the man standing next to him to be a baker as well, to be his second in charge.

He also had a creative way of getting food for the guys. The Commandant had a young son who would chat with him about wanting to learn English, so her father agreed to help him, in exchange for the boy bringing him food scraps from his father's table.

Here he is before he left for the war. Jack S. Dell is in the back row, far left, in the photo below, provided by his daughter. This was likely taken with a group of Australian soldiers before he left Australia for Europe.

Jack S. Dell with soldiers in Australia

Jack S. Dell with soldiers in AustraliaHere's an interesting article about an Australian POW and undercover work at Stalag 13.

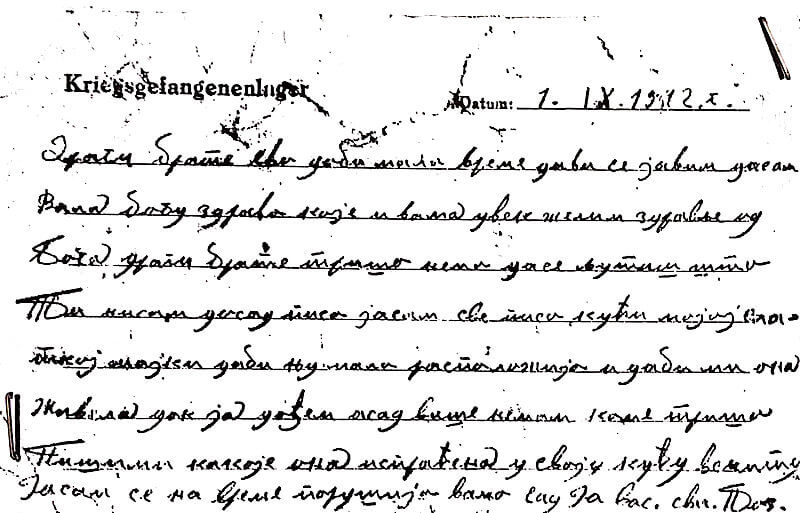

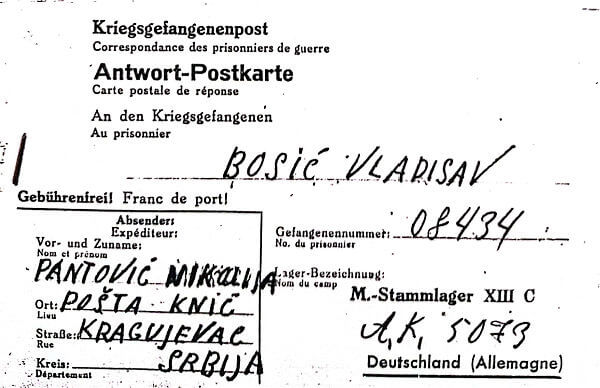

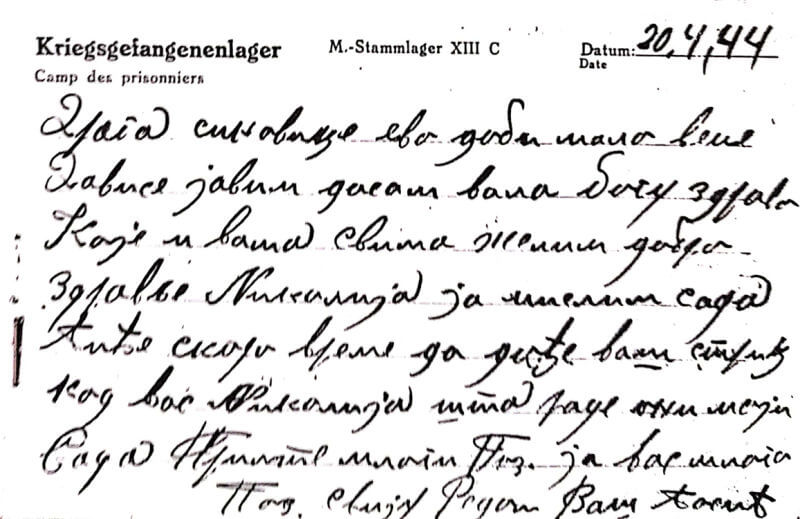

Serbian POWs at Stalag XIIIC

Serbian soldiers started arriving early in the war, in 1941. They were the first POWs in the camp and numbered around 6000.

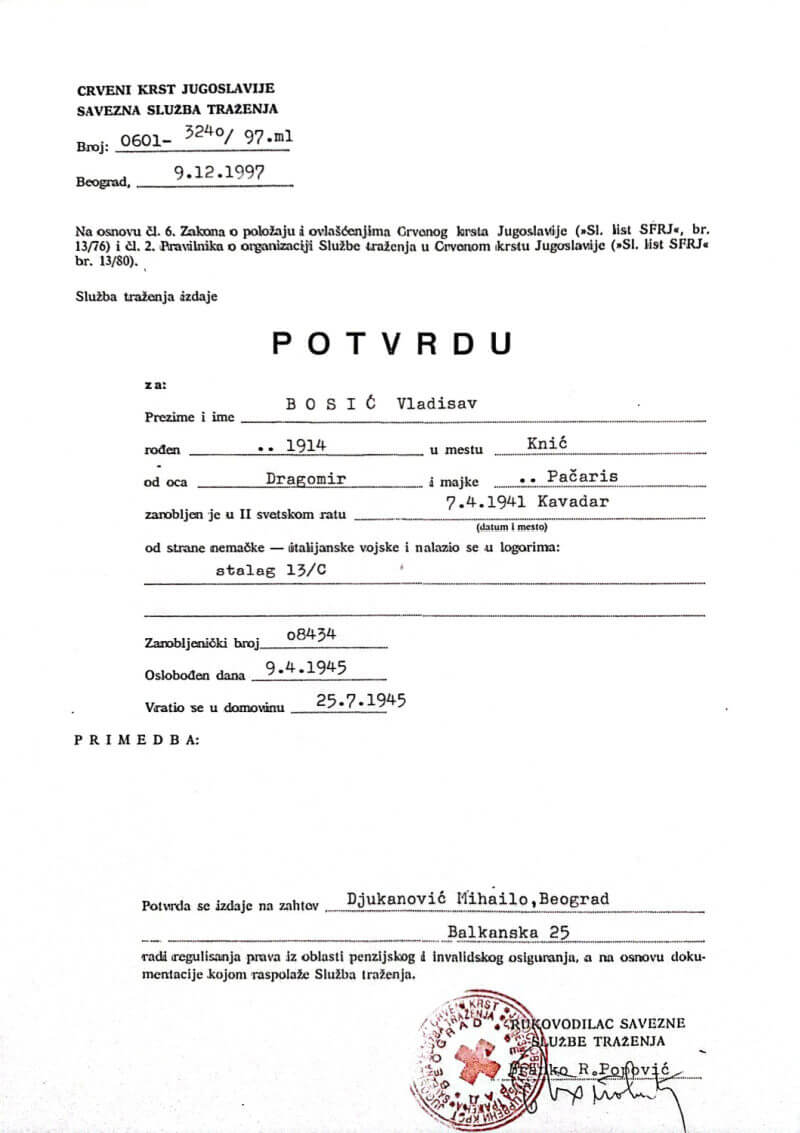

A Serbian artilleryman named Vladisav Bosić was captured in April of 1941 in Serbia and sent to Stalag 13C. He was released in April of 1945 and returned home several months later, according to the Yugoslavian Red Cross documents (see below).

The Serbian soldiers shared their food from their Red Cross packages with the American and Russian POWs in the last months of the war when the supply situation had gotten desperate. (See the Red Cross report on the officers camp, below.)

Vladisav was sent to work in one of the nearby households while he was a prisoner.

His grandson has generously shared a photo of his grandfather taken at the camp, along with copies of postcards he sent from the camp and the Red Cross release document.

Serbian soldier, Vladisav Bosić, on left, with a friend

Serbian soldier, Vladisav Bosić, on left, with a friendThe photo above of Vladisav Bosić and a friend was taken in Stalag XIIIC.

Below are postcards he sent from the camp while a prisoner there.

Front of postcard, September 1942

Front of postcard, September 1942 Text on postcard, September 1942

Text on postcard, September 1942 Postcard from April 1944

Postcard from April 1944

The Yugoslavian Red Cross release form for Vladisav Bosić

Translation:

Red Cross of Yugoslavia

Federal Search Service

Confirmation

Surname and name: Bosić Vladisav

Born: 1914 Place: Knić

Father: Dragomir Mother: Pačaris

Captured in World War II in Kavadar on April 7, 1941, by German-Italian army and found in camp Stalag 13/C

Prisoner number: 08434

Released on April 9, 1945

Returned to his homeland July 25, 1945

Confirmation is issued on the request of .....

(Signed) Head of the Federal Search Service

The town where he was captured, Kavadar, is a small village in central Serbia.

Vladisav's father, Dragomir Bosić, mentioned in the document above, was a POW in World War I. But he never came home and his family never found out what happened to him.

The Officers' Camp

Nordlager Entrance, Oflag 13B

Nordlager Entrance, Oflag 13BThe officers were housed in stone buildings at the northern end of the camp (the Nordlager), separately from the enlisted prisoners, except for a handful of privates and NCO's who assisted the officers.

This camp was called Offizierlager XIII B, or Oflag 13 B.

The officers' camp was divided into two sections: Serbian and American.

In the spring of 1941, 6,000 Serbian officers arrived, and they witnessed the arrival of the Russian prisoners a few months later.

Judging from the large number of Russians buried at the camp (over 3000), the appalling treatment of Russian POW's in general, and a report from a Serbian officer at Oflag 13B, it appears the Russian prisoners were treated very poorly and had a very high mortality rate, unlike most of the other nationalities.

Among the Russian officers arriving in Hammelburg in 1941 was the eldest son of Joseph Stalin, Yakov. He only spent a few weeks in Oflag 13 before the SS came and moved him to another camp.

The Germans offered to exchange him for Field Marshall Paulus. Stalin replied, "You have millions of my sons. Free all of them or Yakov will share their fate." Later, Yakov allegedly committed suicide in Sachsenhausen concentration camp by running into the electrified fence.

The first 300 American officers arrived in the camp on January 11, 1945, soon joined by another 153 officers, all captured on the Western Front during the Battle of the Bulge between December 15th and 22nd, 1944.

In March of 1945, a group of about 490 Americans arrived from Oflag 64 in Poland after marching hundreds of miles in snow and extreme cold. One of the men was Lieutenant Colonel John K. Waters, the son-in-law of General George Patton.

By March 25, 1945, there were 1291 officers and 127 enlisted men in Oflag 13B.

The 11th Hour Raid

By early April of 1945, the Americans had crossed the Rhine and were within 80 miles of Hammelburg. General Patton ordered a special armored task force to go deep behind the German lines and free the prisoners in Oflag/Stalag 13.

Patton later claimed it had nothing to do with his son-in-law being there! He also said it was his only mistake of the war.

John K. Waters

John K. WatersThe men of Task Force Baum, as it was called, ran into heavy resistance coming in but they reached the camp on March 24, 1945. The tanks knocked down the fences, but they also started firing at the Serbian officers, mistaking them for Germans.

Lieutenant Colonel Waters came out with a white flag, accompanied by a German officer, to contact the Americans and stop the shooting. Waters was shot in the stomach by a German guard and was taken to the camp hospital.

The tanks left, accompanied by many of the able-bodied prisoners, but without Waters. On the way back, the Task Force was ambushed and forced to surrender. Out of the 314 men in the unit, 26 were killed and most of the rest were captured. Most of the POW's returned to the camp as well. Lt.Col. Waters survived and eventually retired as a four-star general.

After the failed rescue attempt, the Germans moved all of the Western Allied prisoners to other camps, except the ones in the camp hospital.

Conditions in the Camp

Life in Oflag and Stalag 13 became grim as the war neared its end. The Germans were running out of food and fuel and having difficulty getting supplies for the prisoners.

A Red Cross report following an inspection of Oflag 13B by the Swiss in March, 1945, revealed dreadful conditions.

Daily calories provided by the Germans were 1050 per day, down from 1700 calories earlier. The average temperature in the barracks was 20 degrees F (or -7 degrees C) due to lack of fuel.

Many men were sick and malnourished, and morale and discipline were low. No Red Cross packages had reached the Americans since they started arriving in January. They only reason they didn't starve was the generosity of the Serbian officers, who shared their packages.

To read the detailed Red Cross report, see conditons at Oflag 13B.

The Camp Hospital

The POW camp had a hospital, or Lazarett (military hospital, in German), to take care of sick or injured POW's.

At one point during the war, the camp was run by an Italian medical officer who had been captured by the Germans in 1943. Major Mario Anagni was the director of the camp hospital for some period beginning in July, 1944.

This information was provided by the major's niece, who discovered this from seeing the documents of an Italian soldier, Cinque Antonio di Nola, who had been in the hospital when Major Anagni was in charge there and had requested a certificate of his illness during that period.

The Liberation of Stalag 13C/Oflag 13B

American soldiers at the gates of the POW Camp, 1945

American soldiers at the gates of the POW Camp, 1945 U.S. Army tank arrives at Oflag 13B, 1945

U.S. Army tank arrives at Oflag 13B, 1945The buildings in the above photo still stand. Go to current Stalag 13C map to see where they are now, on the grounds of Lager Hammelburg.

They're inside the restricted area, but can be easily seen from the fence near the main gate.

The prisoners are freed

The prisoners are freedOn April 6, 1945, the 47th Tank Battalion liberated Lager Hammelburg without a fight. Lt. Col. Waters was still there, recuperating in the hospital with some other sick or wounded men. Otherwise, the only prisoners left were the Serbian officers and the Polish and Yugoslavian enlisted men.

One of the American prisoners in Stalag XIIIC at the end of the war was Sergeant Bradford Sherry. His son in the past has posted photos and documents related to his father's captivity; the man on the right facing the camera, shaking hands, looks very much like Sgt. Sherry.

Just after the liberation

Just after the liberation Freed POW's at Stalag 13C

Freed POW's at Stalag 13CSeveral days later, the tank battalion left to rejoin the fighting, leaving a supply unit at the camp. For the next month, no one was in charge of the POW's and there was widespread looting of the surrounding villages, including Hammelburg.

When peace came with the German surrender on May 8, 1945, the Americans returned to occupy Lager Hammelburg and restored order in the town. The remaining prisoners were sent home.

Stalag 13 After the War

The Americans continued to occupy the camp until 1956. They renamed it Camp Denny Clark, after a medic who was killed in action.

The northern part of the Stalag 13 was used to intern former Nazi Party members. The camp also housed large numbers of German refugees who had fled the advancing Russian army in eastern Germany as well as ethnic Germans who had been expelled from areas of Poland and Czechoslovakia.

POW Odds and Ends...

One of the American POW's at Oflag 13 in Hammelburg was Walter Frederick Morrison, the inventor of the frisbee. He was a fighter pilot and was shot down flying a P-47 Thunderbolt. He passed away in 2010 at the age of 90.

P47 Thunderbolt

P47 Thunderbolt(Kogo, GNU FD license.)

were any of the Hogan's Heroes characters based on real people?

The real Kommandants of Stalag 13C between 1940 and 1945 were Lieutenant Colonel von Crailsheim, Colonel Franck and Colonel Westmann.

There was a real life counterpart to the fictional Colonel Robert Hogan in Hogan's Heroes.

Lieutenant Robert Hogan was an American bomber pilot shot down and imprisoned in Oflag 73, companion camp to Stalag 13D, near Nuremberg. To read more about his story, see Robert Hogan.

What about Colonel Klink and Sergeant Schulz? Check out my article on who these characters were based on.

Another Stalag 13...

Stalag XIII B was a POW camp near the town of Weiden, in the Nuremberg area.

The daughter of one of the former prisoners there provides a very interesting account of her father's experience as a Polish POW. More on Stalag 13B.

Report on American POWs in Germany

In 1944 the U.S. Military Intelligence Service published a report on how American POWs were being treated in Germany. To read the report, see POW camp conditions.

The Escape Artists' POW Camp...Colditz Castle

A castle high on a hill in eastern Germany was used to house POWs who had escaped from other POW camps. They were primarily British and British Commonwealth prisoners, and their exploits have become legendary, inspiring numerous films, books and TV shows. See Colditz Castle for more info.

More on Stalag 13...

Share this page: